Jonni Phillips, Expressionist Animation, and Feeling Over Fact.

[via Jonni’s Twitter: https://twitter.com/jonniphillips]

When she was a kid, director Jonni Phillips was fascinated with the American Christian children's cartoon VeggieTales. She was homeschooled, raised in a Christian household, but it wasn’t the fables that interested her.

Something about the way the characters moved, the little countertop sets they designed for their skits, seemed simultaneously so fake that they simply had to be real. Nothing that wore the fact of its computer-generated nature on its sleeve like that could have something to hide.

It’s with this philosophy that Phillips approaches her work: fake makes real.

[I DESPERATELY wanted to include an image from VeggieTales here but their press release site no longer exists apparently]

“I think the way that animation is taught is toxic to artmaking, toxic to trying to express and trying to feel,” she says, referring to the styles of animation taught ad nauseam since early days of traditional animation. Traditionalists - Phillips points out Butch Hartman and Gennedy Genndy Tartakovsky - are trying harder to exist within a historical context than to make something original, she says. “The foundation of all these books was written at this point where there was no such thing as a woman animator, or if there was, they were resigned to the most uncreative role.”

It’s for this reason that many of Jonni’s animation school classmates have trouble getting industry work, even coming from prestigious institutions like Calarts and SVA:NYC. There is some headroom between defying conventions and ending up industry blacklisted, however. Phillips points out artists like Pendleton Ward of Adventure Time fame for making leaps and bounds in the medium of cartoons a lot in the 2010s.

So why break the rules at all?

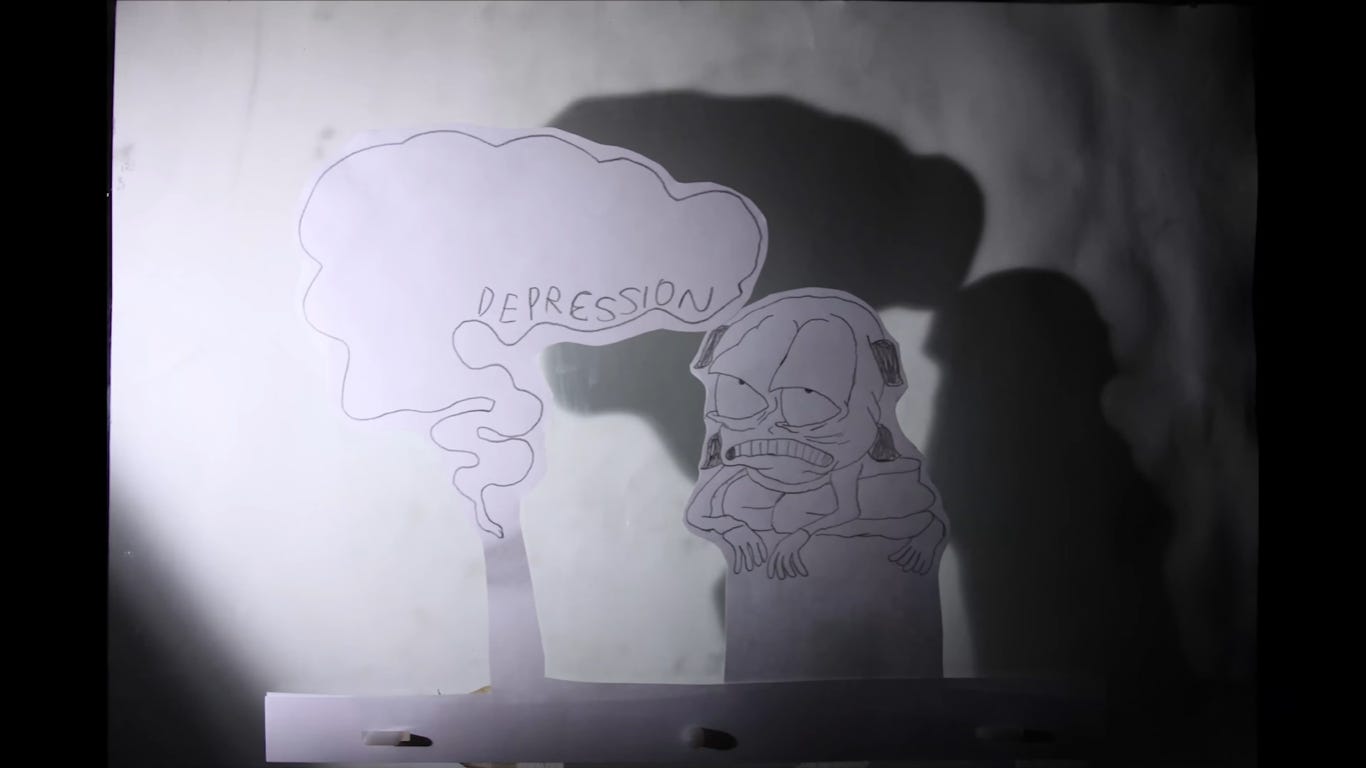

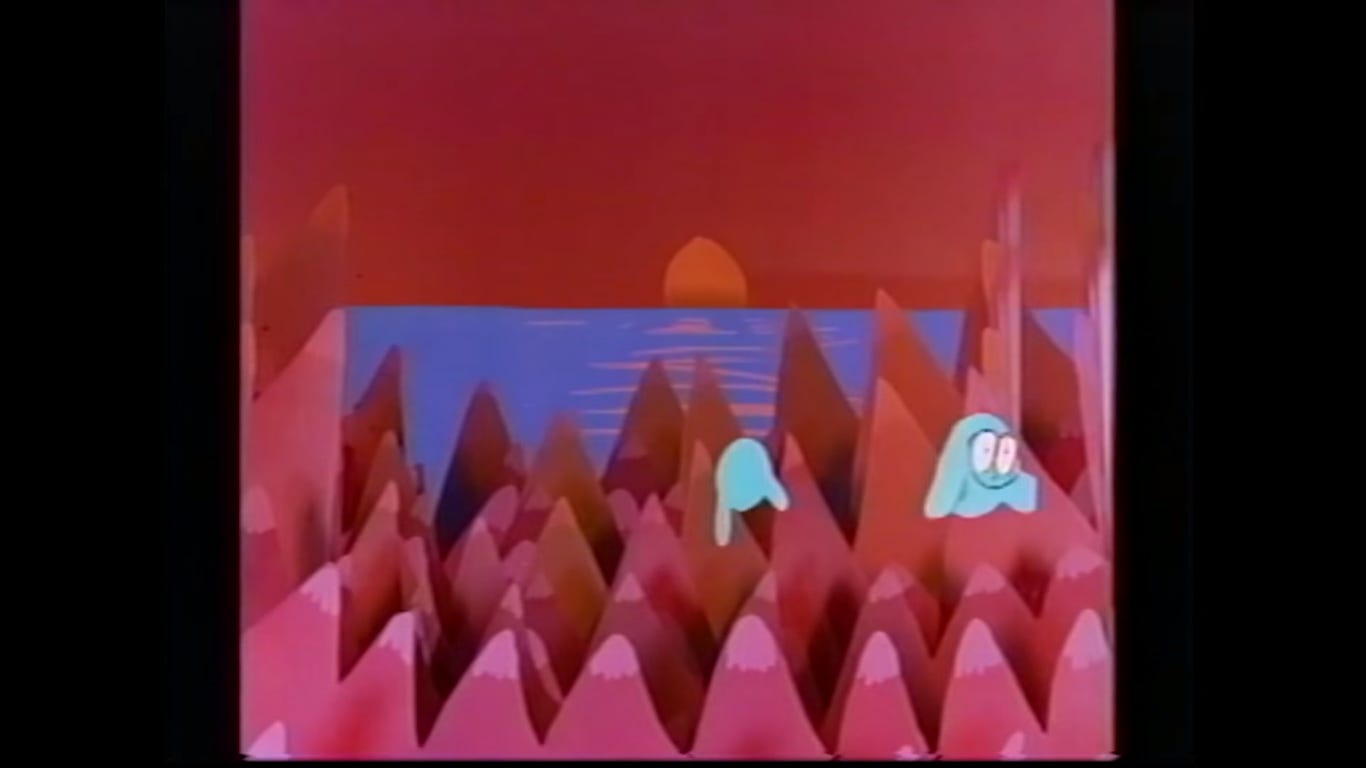

[Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascentia, 2019]

Phillip’s 2019 film: Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascentia explores religious trauma through the eyes of Celisse, a woman who joins a cult and is whisked away to a planet run by her secret mother race: the Scrimbles.

It incorporates many of the hallmarks of Phillip’s style: misuse of an animation multiplane casts shadows from one element to another, colouring is done quickly, leaving scribbles of white between black marks of pencil, there are even points in the film where the stem of an element that connects it to the registration pegs is left in.

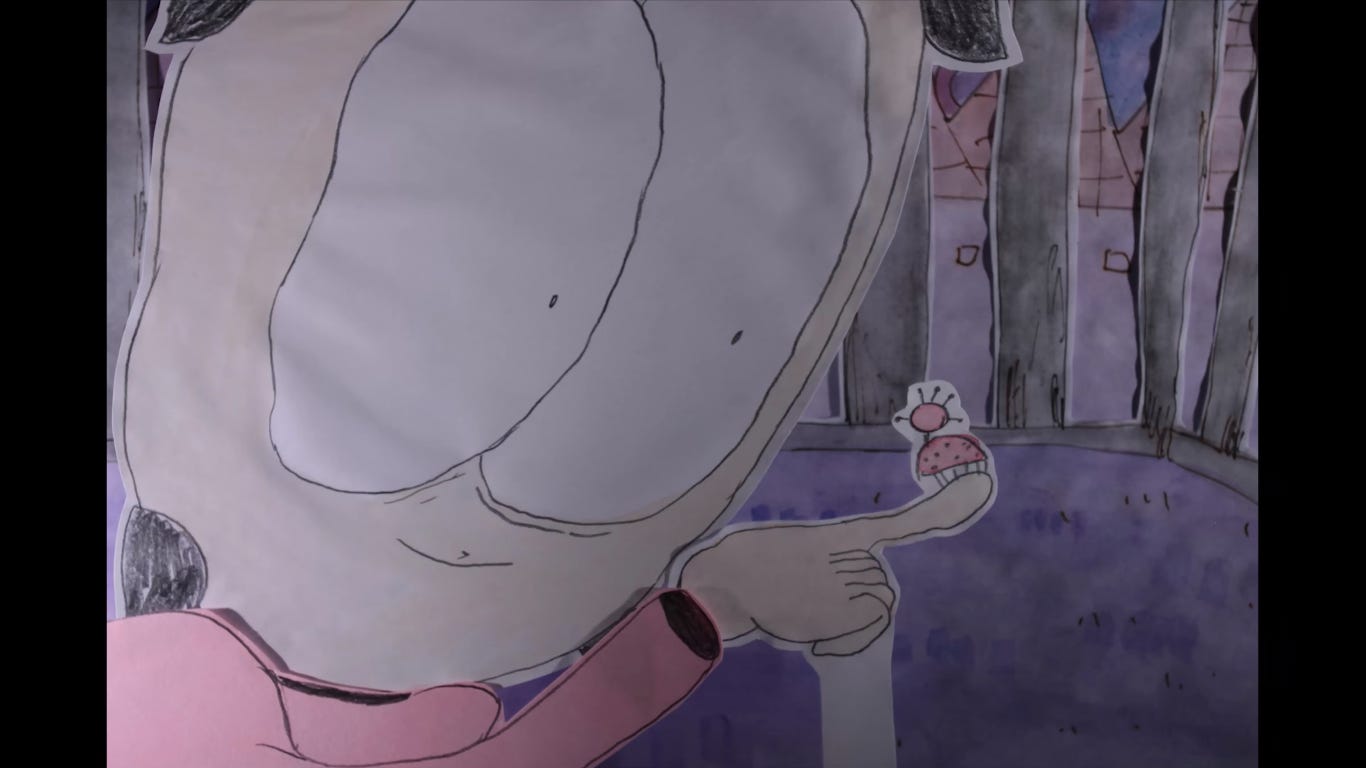

[Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascentia, 2019]

None of this is done out of laziness, it’s all in service of what Phillips calls “emotional documentaries”:

“I try and capture certain emotions or certain points in my life and make a world that is made out of those things [...] informed by how things feel rather than what they are. They’re also cartoons, that’s a thing.”

If anything, it’s a shortcut to connecting with the audience. The crux of Ascentia is bringing the viewer onto the side of unreality. Like Veggietales (unintentionally), Phillips (intentionally) presents upfront what is ‘fake’ about a piece: it is animated, acted, and ultimately unreal.

This creates a fantastic contrast to what is ‘real’ about it: a tight and personal story, made all the more real in the explicit knowledge that a small team of human people cut each individual frame out of cardstock and printer paper to lie down between sheets of glass.

The Disciples of Ascentia are based loosely on Heaven’s Gate, a fringe religious organization that left tapes behind just before a mass suicide.

“I would go into the comments of these Heaven's Gate videos,” Phillips says, “and they’d all be like ‘these people are so fucking stupid’ and ‘how could they believe something so dumb’.”

In Jonni’s eyes, the victims of Heaven’s Gate, and The Disciples are not stupid people, but people who crave structure. Where most comparisons between mainstream religion and fringe cult religions take the form of mocking either group, Phillips tackles the structure itself.

“After a while of observing how ridiculous a lot of our parents' rules are, it starts to become really funny. Everything is a joke [...] All the problems of being in the Wasteland follow them to the Scrimble world. They’re not different people.”

Celisse is the only character who becomes happier through the course of the film because she prioritizes the feeling of being with her newfound family over the fact of being imprisoned on an alien planet. “Even at the bottom of society she’s still finding moments where she isn’t miserable.” says Phillips.

[Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascentia, 2019]

Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascentia is the third in a series of five films titled Wasteland. The second of which - Goodbye Forever Party - presents the most accessible interpretation of these ideas. It is also the most directly autobiographical of the series.

[Goodbye Forever Party, 2017]

In 2015, at age 18, Phillips pitched a pilot to Frederator Studios called Rachel and Her Grandfather Control the Island as a part of their GO! Cartoons series. Phillips landed the pitch, and Rachel and Her Grandfather came out two years later.

What defines that experience for Phillips is aspiration. She wanted so badly to be “the next Adventure Time” after getting the opportunity to work with its original creators, that she was miserable the entire time, trying to be something that she wasn’t.

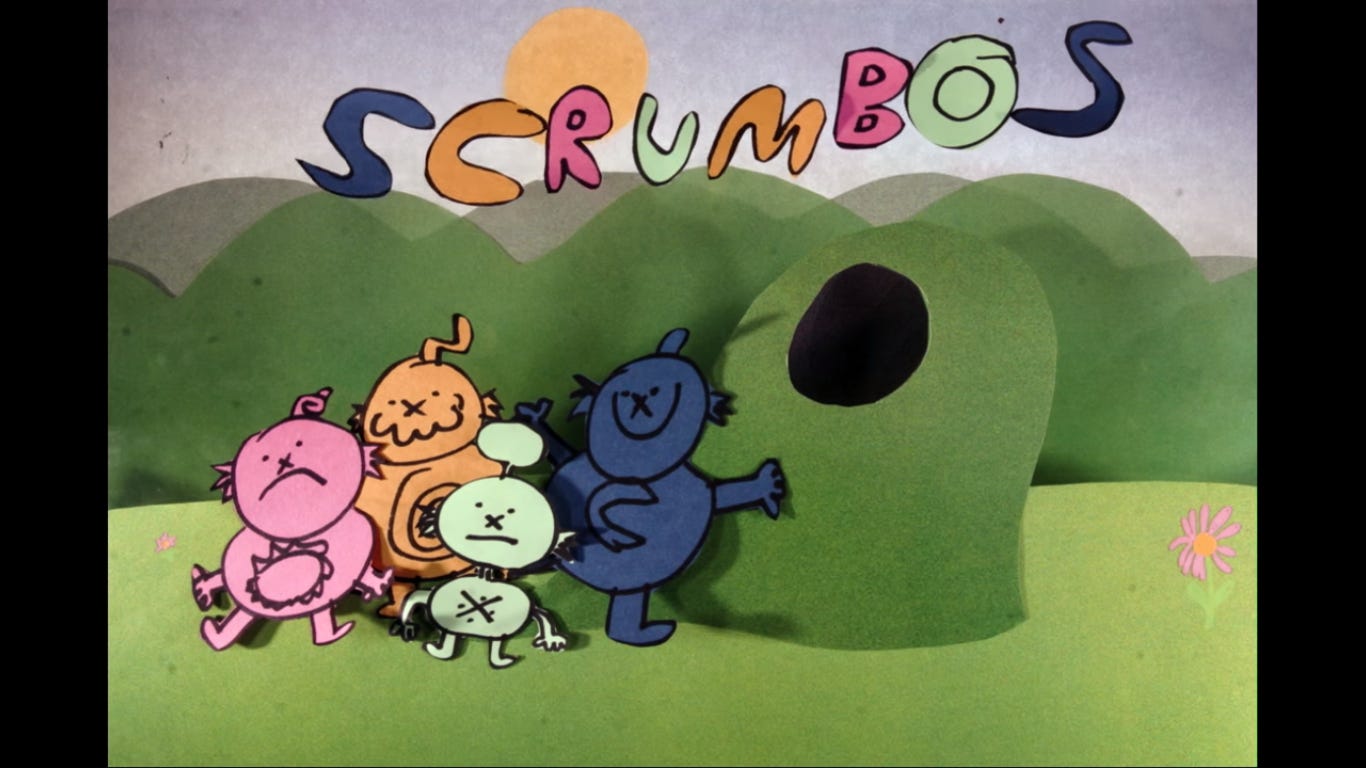

Lilith - the main character of Goodbye Forever Party - works for a TV studio, playing one of the costumed characters in a children’s television show modelled after the Teletubbies called Scrumbos. Her mental health and ability to connect with others suffers at the hands of director Von Soupton, culminating in her packing up, changing her name, and leaving the Wasteland.

Lilith is free from her personal Wasteland in the same way that Jonni was freed from hers, by being, rather than aspiring. “I’m the kind of filmmaker that I say I am, I know what I want to do, and so artistically I’m super fulfilled. Whenever I say ‘I am this filmmaker’, ‘I am this’, ‘I am whatever’ great things happen every time, y’know? I make another movie or I feel great,” she says.

[Goodbye Forever Party, 2017]

“Most of my work is trying to really legitimize feeling over fact. My relationship with gender is feeling over fact. I am someone who is feeling over fact.”

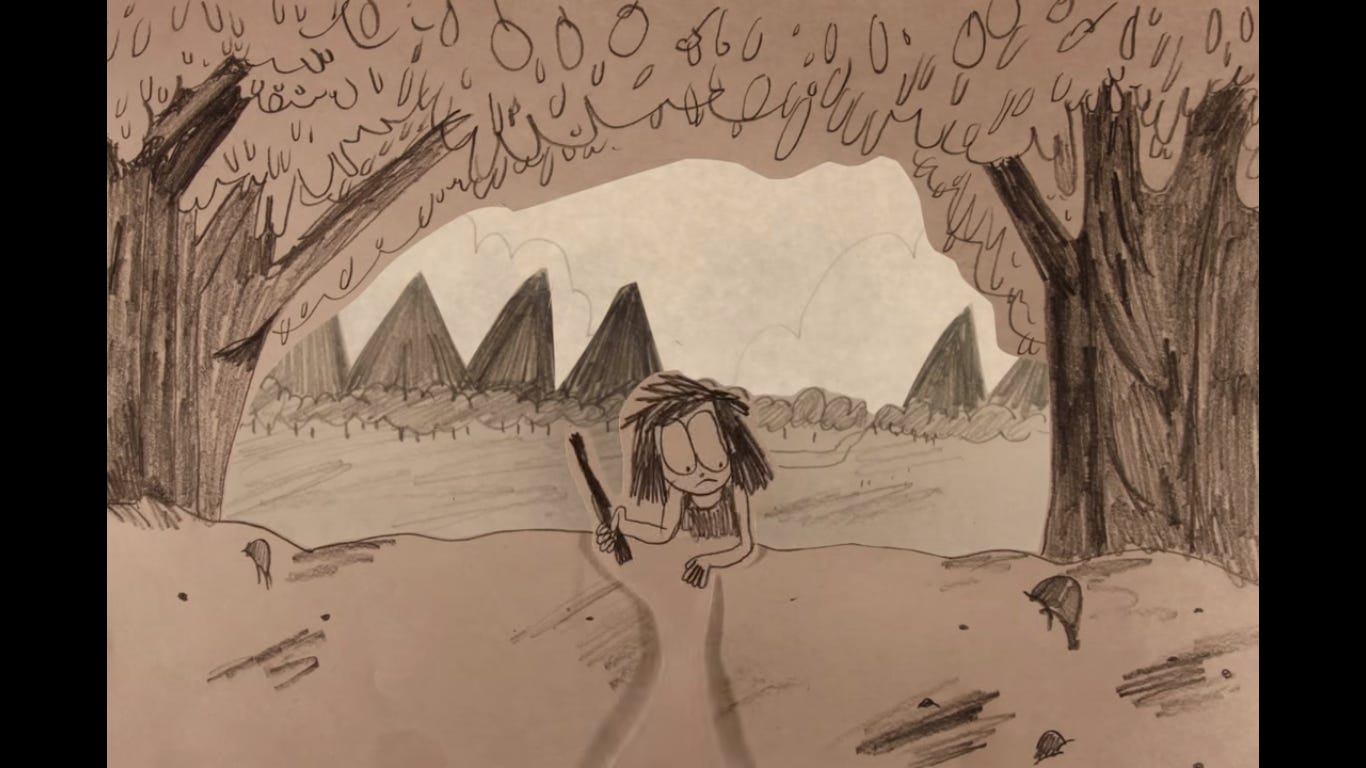

If any of this is understandable, it is through the lens of Phillip’s first-year film, titled: The Earth is Flat, about a woman who meets a flat earth believer at a coffee shop. For days on end, it challenges her most fundamental belief about her world until, relaxing after a long day at work, she lies back and accepts that she will truly never know. In her own words:

[The Earth is Flat, 2016]

“I don’t literally think the earth is flat, but emotionally I kind of do. The pure simplicity of the earth being flat is really comforting, the spirit- whatever’s inside me really likes that.”

Phillips is currently working on a new film, the prequel series to which can be found on her YouTube channel.